A Spark in the Dark: Shedding Light on the Origins of Fire-making

Our personal relationship with fire has become greatly diminished in the modern era compared to our prehistoric ancestors. Save for gas stoves, candles and the occasional barbeque, fire is not often something we experience day-to-day as it would have been in the past.

Yet fire remains the basis for the vast majority of our technology and comforts, despite being largely hidden away. Without distant coal-fired power plants, internal combustion engines, furnaces and the like, life as we know it today could not exist. It is for this reason that the development of fire as an adaptive tool by humans is of such interest to us all. Determining when and how fire entered our technological repertoire is key to understanding who we are as a species, and as a society.

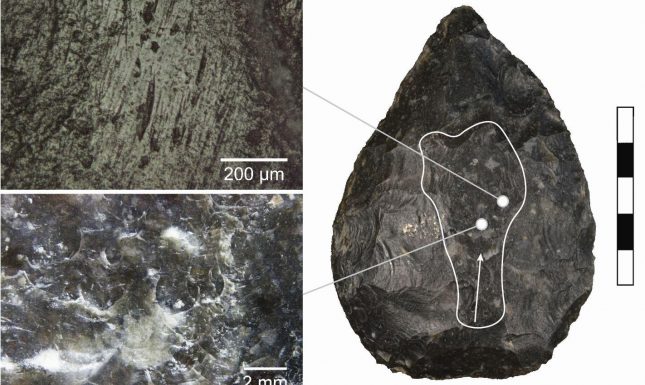

Hi, there… my name is Andrew Sorensen, and I defended my PhD in Palaeolithic Archaeology and Material Culture Studies at the Leiden Faculty of Archaeology back in December 2018. More recently, I was awarded a Veni Innovational Research Incentives Scheme Grant from the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO). My research focuses on fire use by Palaeolithic peoples, including the identification of ancient fire-making tools using experimental archaeology in combination with microwear analysis. This work is primarily concerned with the stone-on-stone fire production system, so using pieces of flint as ‘strike-a-light’ tools to strike the mineral pyrite to produce sparks. These sparks are directed onto easily flammable tinder materials which begin to smoulder once a spark has been ‘captured’. This process leaves distinct mineral traces on the flint strike-a-lights that can be observed using a microscope.

Using experimental fire-making tools, I am able to reproduce these pyrite traces and then compare them to mineral traces found on archaeological tools to determine if they are similar or different. Using these methods, I have been able to identify mineral traces on dozens of Neandertal bifacial tools (or handaxes) from France that look very similar to the pyrite traces on my experimental tools. These Neandertal bifaces are all around 50,000 years old, making them the oldest probable fire-making tools in the world! These tools support the idea that Neandertals were proficient users of fire, able to make it when and where they wanted to for cooking their food, warming themselves or even for producing birch bark tar for making tools.

My current Veni project will apply these same concepts to the early Upper Palaeolithic (ca. 45,000–20,000 years ago) when warm-adapted modern humans (Homo sapiens) replaced Neandertals in Ice Age Europe. The archaeological record tells us these peoples were proficient users of fire, but the evidence that they could make fire themselves is lacking. Nevertheless, researchers tend to assume they could do so. My project will test this idea first by compiling a large database of early Upper Palaeolithic sites exhibiting evidence that fire was used on-site (i.e., hearths/combustion features, charcoal, fire-affected flint and bone artefacts, etc.) in an effort to determine when and how fire was used by these peoples and if these practices changed over time with shifts in climate or between cultural groups. I will then try to address the apparent lack of fire-making tools from this period through systematic analysis of archaeological stone artefact assemblages in search of flint strike-a-lights and pyrite specimens using the methods described above.

The ability to control fire is a pervasive human trait which influenced both the biological and cultural development of our evolutionary lineage. This ability made uninhabitable climates tolerable, inedible foods palatable and provided a new focal point for social interaction (much like television does today). When exactly humans or their ancestors developed the ability to use fire, and later to produce it, is still a source of considerable debate and is directly relevant to wider discussions in evolutionary and social anthropology, human cognition and the mechanisms behind the multiple instances of hominin migration into temperate and Ice Age Eurasia. In my continued ‘Quest for Fire’, I hope to shed more light on these vexing issues.

0 Comments