Changing tastes through time: A foodlab at Paleis Het Loo

In the foodlab at Paleis Het Loo, we tried to find out how current tastes compare to those of premodern times.

Written by Milena Blokzijl, Julia Drijver and Anne-Maartje Lobregt, edited by Prof. Dr. J.A.C. Vroom, 2023. The project was supervised by Prof. Dr. J.A.C. Vroom.

Food trends differ over time. Some flavours enjoy popularity only for brief periods of time, like the jellied dishes from the 1970s or seasonal flavours like pumpkin spice. But how do our current tastes compare to those of ages past? The seventeenth century in the Netherlands was an interesting period food-wise. Dutch cuisine was increasingly influenced by the overseas trade of the VOC, which in turn triggered an interest in local produce. So how do our current tastes compare to the popular flavours of the seventeenth century? This is what we aimed to discover during Leiden University’s seventeenth-century Foodlab at Palace Het Loo.

Introduction

In October 2022, we held a seventeenth-century Foodlab at Palace Het Loo in Apeldoorn as part of their exhibition “Heerlijke Herfst” (Appetising Autumn). This was the newest Foodlab in the series of Foodlabs organised in the last decade by Professor Vroom from the Faculty of Archaeology. During last year’s Foodlab, we presented four recipes taken from the seventeenth-century cookbook “De Verstandige Kock”. The cookbook was very popular among middle-class Dutch citizens. The recipes were created with the help of chef Youssef el-Abassi from makingfoodhistory.nl. The recipes were a savoury pastry, a sweet berry tart, a marmalade and a hot cocoa drink.

The Palace was built in the late seventeenth century as a residence for King William III and Mary II. Here, most of the recipes presented at the Foodlab will have been consumed by the inhabitants of the palace. The recipes all contained ingredients that made them a product of their time, especially in their use of exotic spices, as well as local products that were grown on the grounds of the Palace.

The savoury pastry, containing parsnip and mushroom, signalled the returning interest in local produce, which may have been a response to the increased long-distance trade. The addition of cloves and puff pastry, however, signals the high status of the pastry, as cloves were sourced from the Maluku islands, and puff pastry was very labour-intensive to make.

The berry tart contained several forest berries as well as almond paste and a high amount of sugar. These last two ingredients made the tart a luxury product. The tart we served was based on a seventeenth-century painting.

The marmalade contained orange, lemon, mint, ginger and sugar and was based on a seventeenth-century recipe. Most of the ingredients were imported from abroad, and the recipe was a summer delicacy for the upper and upper-middle class.

The cocoa drink contained ground cocoa nibs, cinnamon, cloves, nutmeg and anise, but notably no sugar or milk. The drink was a very expensive luxury product at the time, with all ingredients being sourced from the Dutch colonies as well as the Americas. The drink was also mostly used to impress guests. Based on these recipes, visitors were asked to taste the food and fill in a questionnaire regarding their opinions on the recipe. Through this project, we wanted to analyse how our tastes may have changed through time and if our associations with certain flavours may have changed from a modern viewpoint.

Results

During the tasting at Palace Het Loo, the visitors participating in the tasting had to fill out a questionnaire. The answers to these questions were the basis of our database.

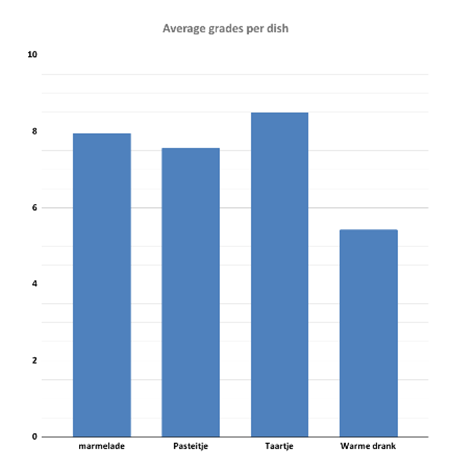

In total, we had 3,271 people participate in this iteration of Foodlabs. Of these, 2,990 responses were for the original four recipes: the sweet tart with 1,124 responses, the savoury pastry with 884 responses, the warm drink with 635 responses, and finally, the marmalade with 347 responses. The other responses concerned two alternative recipes, which will be discussed later in this article.

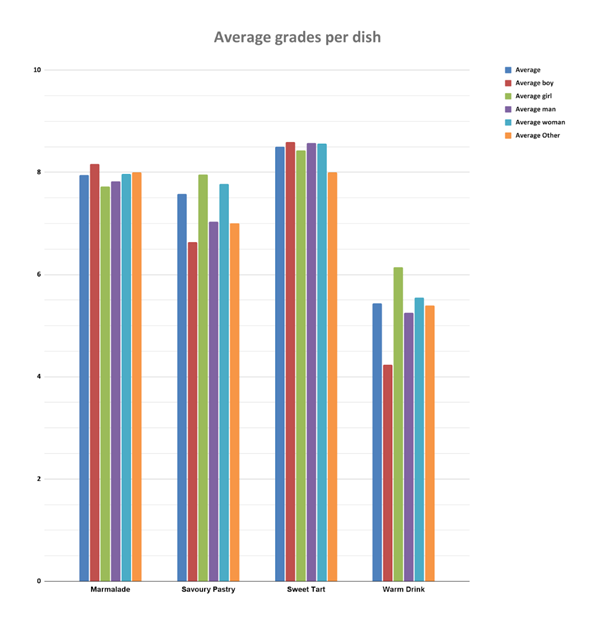

The fruit tart received the highest average score of 8.50, while the marmalade scored 7.95, indicating the popularity of sweet dishes in general. As expected, the warm drink received the lowest score of 5.43, which could be attributed to the absence of sugar. The spices such as nutmeg, cloves, and cinnamon gave the drink a flavour reminiscent of winter-esque drinks, similar to hot chocolate or mulled wine. However, it had a bitter taste, unlike the sweetness we are accustomed to. It was more similar to the bitterness found in coffee or strong tea. Interestingly, girls awarded the drink a high score of 6.14, while boys gave it the lowest score of 4.24 (both study groups were near-equal in number). Girls even gave the dish a higher grade than adults, which is especially strange considering one would expect adults to be more accustomed to bitter drinks like coffee.

We observed a relatively even distribution among age groups, with a peak in those aged between 41 and 60. However, the number of visitors above the age of 71 was notably low, especially those above the age of 81. Our conclusions were drawn based on a broad distinction between those over the age of 18 and those under 18. Among all the groups, women awarded the highest grades, comprising 50.9% of the participants. Men made up 30.8% of the participants, while girls and boys accounted for 9.5% and 8.3%, respectively.

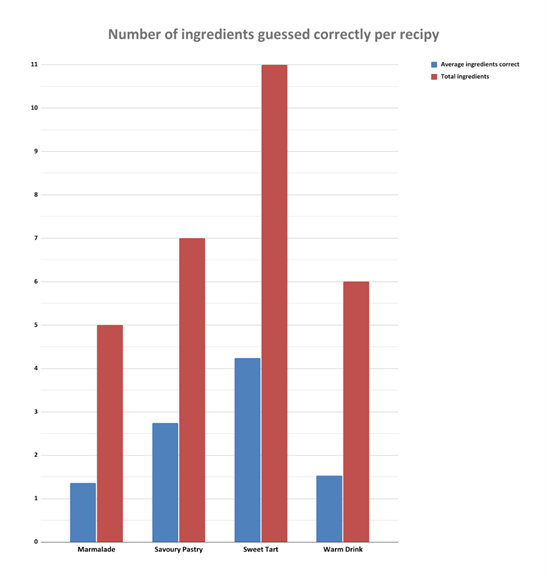

Additionally, 0.5% of the participants were classified as other. An interesting observation was that boys tended to give higher grades to the sweet dishes, whereas girls gave higher grades to the savoury dishes. A significant dataset for our research aim was the number of correctly guessed ingredients. In the chart below, red signifies the total number of ingredients per recipe, and blue represents the average number of correctly guessed ingredients.

It proved difficult for people to guess more than half of the ingredients used in the dishes. The fruit tart was the easiest to recognise, thanks to the visible berries and the recipe's familiarity. However, the cocoa drink was challenging for people to discern because of the high number of spices used. While some people recognised nutmeg or cinnamon, anise was often not identified in the beverage. Even the cocoa nibs were often overlooked because of their very different taste compared to modern chocolate. Although many people identified orange as the main ingredient in the marmalade, it was also frequently mistaken for apricot or peach. The addition of honey was also expected. The sweetness of the fruit and honey, along with the mint and ginger, slightly concealed the orange's flavour.

Results: Alternative recipes

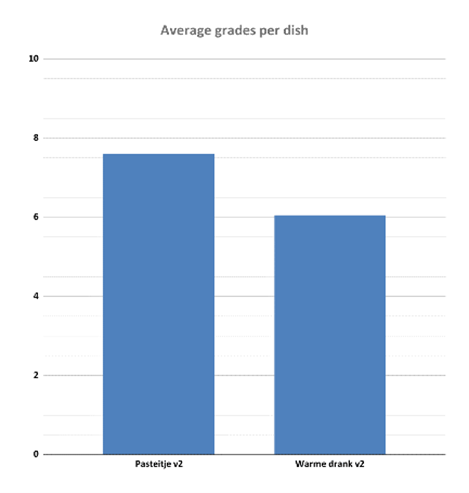

Apart from the four original recipes, two had been altered slightly. These dishes were only served for a short period of time but still resulted in a total of 281 responses.

The first adapted dish is the hot drink. This was sweetened with more sugar, and chocolate was used instead of cocoa nibs, which made it more appealing to modern tastes. People seemed to like this version more, as the grade it received increased from a 5.4 to a 6.1 on average. Despite this improvement, the drink still proved to be the least popular dish. This was likely caused by the use of water instead of milk, as is done in modern-day hot chocolate drinks.

The savoury pastry was changed by adding more spices. However, this did not result in a change in the grade awarded by participants, as shown in the graphs below (Figure 4, Figure 5). While people more often recognised the use of spices, they did not necessarily recognise what spices were used. It seems this changed recipe did not improve the taste of the pastry significantly. However, more people assumed the pastry included meat with the addition of more spices.

Conclusion

The Foodlab at Palace Het Loo was meant to help us further our understanding of the way our tastes have changed between the seventeenth century and today, especially regarding the associations the flavours instilled in the consumer. We gathered over 3000 responses from a broad public. The data analysis proves that our tastes have generally changed to favour sweeter recipes over heavily spiced ones, as evidenced by the popularity of the fruit tart and the marmalade. This is also evidenced by the increase in the grade given to the version 2 cocoa drink, which had a higher sugar level and used chocolate rather than cocoa nibs. One curious result was that girls seemed to favour savoury dishes more than boys would, as well as the comparatively higher scores they gave to the hot cocoa drink. It may be interesting to review if other factors, such as age or nationality, could have influenced this distinction. Identifying the different ingredients proved difficult for the respondents. This may be caused by the decrease in the use of some products, like parsnip, or by the general lessening of people cooking with fresh ingredients instead of pre-made recipe sets or spice mixes. The cocoa drink’s many spices were difficult to discern, likely caused by its stark difference from modern-day chocolate milk. The analysis of the alternative recipes in version two seems to indicate that an increase in spices does not necessarily increase the grade people awarded to the pastry. A general lower appreciation of exotic spices is likely caused by the ready availability of these nowadays compared to in the seventeenth century. It may be interesting to analyse if age and/or nationality may have influenced people’s ability to recognise specific ingredients.

Overall, we can say with certainty that our preferred flavours have changed from the seventeenth century, living in a world with more processed foods.

Source

Willebrands, M. A. van Dongen & M. Henzen. (2022). De verstandighe kock: Proef de smaak van de 17e eeuw. Sterck & de Vreese.

© Joanita Vroom et al. and Leiden Medievalists Blog, 2023. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Joanita Vroom et al. and Leiden Medievalists Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

0 Comments