Water in the Desert? The Oxus Civilization and the role of the irrigation system

A “hidden” region to Western eyes

Last year, 2021, marked the 30th anniversary of independence from the Soviet Union of most Central Asian republics. During the “Great Game” in the 19th century, Central Asia saw a vibrant presence of many Western and Russian official diplomats, such as Arthur Conolly and Nikolay Przhevalsky, along with the presence of many geographers, explorers, topographers, and archaeologists whose real role and missions were often undercover (1). The establishment of the Soviet Union and the erection of the Iron Curtain marked the end of any non-Soviet presence in Central Asia, including Western archaeological missions. As a result, Western scholars neglected this region for more than 70 years. They considered the area to be of no great interest in archaeological terms while concentrating their investigation in Western Asia. In the U.S., it was only in the fall of 1981 that, at Harvard University, the first symposium that saw the presence of U.S.S.R. delegates was organized. Despite the rules applied to U.S.S.R. colleagues, who had to strictly follow the program meticulously organized by the U.S. State Department for security reasons, the symposium was a great success. As such, three more conferences were held in Samarkand, Washington, and Tbilisi in the following years, and Western archaeological missions in Central Asia started to be established in collaboration with Soviet institutions. The legacy of these projects continued after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Today, many more joint projects, with local partners and institutions, take place in the region during the year.

The Oxus Civilization: an (un)expected discovery

As a young student interested in the archaeology of Western and Central Asia (and very passionate about the Great Game), I first joined the Uzbek-Italian Archaeological Project in Samarkand and then, a year later, the Turkmen-Italian team of the Archaeological Map of Murghab Delta Projects

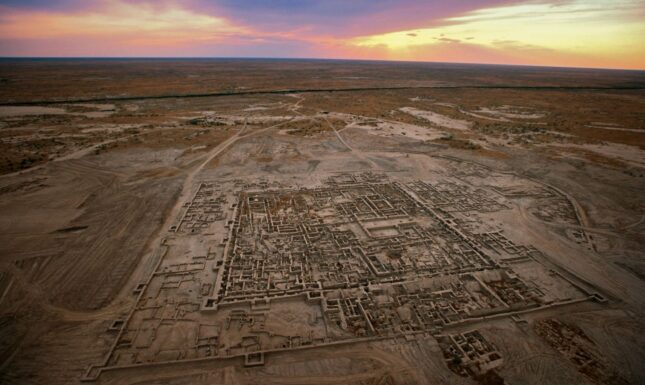

in southern Turkmenistan. The Murghab (Fig. 1) is one of the core areas of the Bactria–Margiana Archaeological Complex (BMAC), also known as the Oxus Civilization. Located in the heart of the historical Silk Road, it is a place where archaeological teams have uncovered magnificent citadels, such as Gonur Depe (Fig. 2), and unique material culture dating back to the late third and early second millennia BCE (2). During the early stages of archaeological research in the 1950s and 1960s, it became clear that the Murghab region, with its large urban complexes, had close interregional contacts with places as far as Iran, the Indus Valley, the Persian Gulf, and Mesopotamia. During my stay as a student in Central Asia, I became more interested in this early civilization and the magnificent discoveries within it.

Crucial to the emergence of this urban civilization was the Murghab inner delta. With its present extension of more than 25,000 km2, the Murghab is considered one of Central Asia's most important inland deltas. The northeastern area of this region is mainly dominated by desert and semidesert landscapes (Fig. 3). However, the 1980s marked the final construction of the Karakum Canal, which brought water from the Amu Darya river (ancient Oxus) to the Murghab, increasing the Murghab’s delta capacity. Considering its arid landscape, which likely originated during the Bronze Age, scholars have long argued for the importance of water as a resource in the rise and development of the BMAC. However, crucial aspects of the impact of agricultural and water management in the civilization’s development remain largely underresearched.

Archaeobotanical investigation informs us that the BMAC urban centers in the Murghab were rich in barley, wheat, and legumes, such as peas and lentils, but grapes were also commonly cultivated at the end of the third millennium BCE. However, how did local communities adapt their agricultural practices to this harsh environment during the Bronze Age? How did they manage their water resources, and where were ancient irrigation channels located? Did the distribution of the settlements across the landscape take into account the available water resources? In addition, was there a difference in terms of water resources between urban centers and peripheral settlements? Building on previously acquired knowledge of the ancient landscape, my PhD research aims to investigate how ancient irrigation networks and water resources shaped local agricultural and settlement patterns and how the system changed during the third and second millennia BCE in the Murghab. To answer my research questions, I applied a microscale multidisciplinary methodology to two local areas in the Murghab. I specifically focused on reconstructing, surveying, and dating ancient watercourses and related archaeological sites.

Walking into the desert looking for ancient water traces

The first stage of the research was desk based, involving the reconstruction of the ancient channel system through the analysis of satellite and aerial images. The traces of ancient water channels, with their meanders, are often visible on these images, providing a preliminary analysis of the ancient hydrological system. However, this reconstruction needs to be validated on the ground. Therefore, we surveyed the reconstructed ancient watercourses during fieldwork in Turkmenistan to verify their presence and structures (Fig. 4). A fieldwork survey, however, is also crucial to date the ancient channels by their association with settlements. This provides a reasonable estimate of when these channels were active. As such, during the survey along the former channels, diagnostic archaeological materials were collected, and more than 20 new sites were recorded along the channels, which helped to establish a first relative chronology of the system. However, a diachronic stratigraphic sequence of the ancient channels was crucial to better understand the link between human occupation and water resources. This was obtained by excavating test trenches in the beds of former channels and using a hand auger (Fig. 5). A hand auger is a tool that penetrates the ground and permits the investigation of the stratigraphical sequence of a given surface without excavating. However, the excavation of test trenches in selected ancient channels was crucial to collect samples for precisely dating the sediments and expand our knowledge about the history of the channels and how they evolved.

The preliminary results showed that this desert area was much more watered during the Bronze Age, with the presence of several primary and secondary channels. Likewise, local communities had specific knowledge about the use of these channels. They targeted specific waterways for opportunist farming, while primary or more stable channels around urban centers were used for more secure cultivation. To conclude, the present ongoing investigation aims to shed new light on the evolution of the agricultural and water management systems of this early civilization in a region that has often been overlooked by Western archaeologists.

Notes

(1) To further explore this topic:

- Peter Hopkirk (2006). The Great Game: On Secret Service in High Asia, John Murray-reprint edition.

- Peter Hopkirk (2006). Foreign Devils on the Silk Road: The Search for the Lost Treasures of Central Asia, John Murray-revised edition.

(2). To further explore the topic on Oxus Civilization:

- Lyonnet B. and Dubova A (2021). The World of the Oxus Civilization, London: Routledge.

0 Comments