Bringing the Past into the Future

Working with Urbanists to Design a new Landscape in Mérida, Yucatán

How can archaeology still be relevant today? This is a question I am sure many archaeologists have been asked at some point in their career. Archaeology is often seen as simply ‘digging into the past’; unearthing old ruins, excavating burials, deciphering ancient texts. Yet, it is the insights gained from this past that can tell us so much about how to engage with our present, and our future.

Designing sustainable, regenerative urban landscapes

In June 2025, I had the privilege of taking part in a multidisciplinary workshop taking place at the Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán (UADY) in Mérida, Mexico led by Dr Benjamin Vis (Université Libre de Bruxelles), Prof. Rob Roggema (Tecnológico de Monterrey), Nahuel Beccan Davila, and Esteban Martínez Hernández. In a collaboration with the Université Libre de Bruxelles and Tecnológico de Monterrey, this workshop was designed to bring together archaeological understanding of prehispanic Mayan land use, water management, and urban patterns with the modern needs and characteristics of local communities living in the area today. Archaeologists, anthropologists, architects and urbanists came together to design sustainable, regenerative urban landscapes that not only revitalise traditional lifeways, but also allow local individuals to build towards a resilient future.

This workshop focused on three case studies in the Mérida area: Caucel, Komchén, and Kanasín. Each presented a unique context, demanding unique design strategies. Three days of fieldwork in each site were followed by an intensive design charrette, using the research-by-design methodology. As an archaeologist collaborating with urbanists, I was able to provide insight into the social and cultural landscapes of the past and present, and how these must be taken into account in modern urban design. We must design not just for the space, but for the people, too.

Phase 1: fieldwork

The first phase of the workshop consisted of three days of fieldwork, one in each site chosen as a case study. The group, consisting of the four co-leaders of the project as well as urbanism students from Tecnológico de Monterrey and anthropology students from UADY was split into three teams each focusing on a different aspect of the site: ethnography, urbanism, and interviews.

The ethnography team, of which I was a member, was tasked with exploring the town from an ethnographic perspective, analysing elements such as the use of traditional techniques and materials, similarities in the ways contemporary communities and past peoples of the area interact with their landscape, and the continuation of (parts of) the solar household structure, which was common in prehispanic Mayan urban landscapes and which has seen considerable continuity of tradition in Yucatán despite colonial efforts at enforcing conformity. We observed a lack of connection with local prehispanic heritage, evidenced by a lack of maintenance of Mayan archaeological remains which were often covered in beer bottles, clothing, and other waste. Despite older anthropological and ethnographic sources attesting to the continuation of the solar structure as well as traditional thatched roof architecture styles, we found but a few examples of this in the field, demonstrating the continued imposition of both private and public standardised urban expansion with no regard for local needs. Nevertheless, many inhabitants persisted in their cultural practices, continuing to grow and sell their own fruits and vegetables, keep livestock, and maintain traditional techniques of burning waste. This shows a remarkable cultural resilience, calling for a design that will allow this to flourish as it used to.

Meanwhile, the urbanists explored the town from a spatial perspective, looking at urban design, layout, division of public and private spaces, and more. The interview team was tasked with speaking to local inhabitants in the main plaza, learning about the ways their home had changed over time as well as what their priorities, needs, and desires were for a potential new urban design.

We collected all the insights gained from fieldwork in order to determine what key aspects of each case study would need to inform our design choices later on. Each site presented a unique context, and the design solutions that would suit this context needed to be curated to the specific conditions we observed in the field.

Phase 2: research by design

Following the fieldwork, we conducted a four-day design charrette aiming to build creative design solutions to the problems observed in the field through integrating past strategies with contemporary urbanism. This charrette made use of the ‘research-by-design’ methodology, in which researchers are able to combine the analysis and design processes in one approach, allowing both aspects to continue developing alongside one another and enabling adaptable and reciprocal design.

The group reconfigured into three new teams, combining members of the ethnography, urbanism, and interview approaches into mixed groups creating one design for each of the three case studies. In my case this was Komchén. The combination of members from different backgrounds allowed us to create truly interdisciplinary design, and ensure that all aspects of each site and of past land use were incorporated.

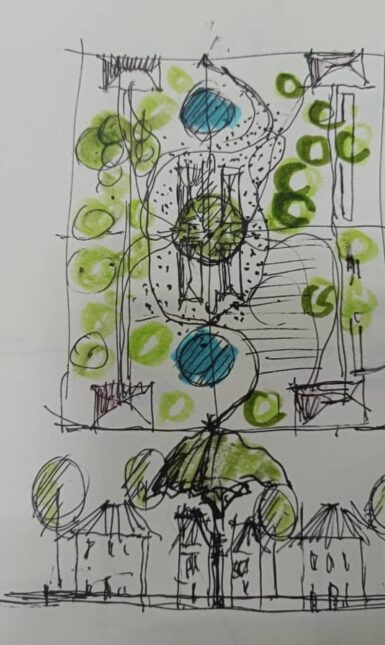

The goal for each team was to create a new urban design at three different scales: the whole site (masterplan), the middle scale (neighbourhood), and the detailed scale (individual blocks). We aimed to take inspiration from past land use strategies while also enhancing ecological qualities of the space, with the ultimate focus being on creating a liveable and connected urban space for local inhabitants. As one of the few non-urbanists present, I attempted to emphasise the social and cultural aspects of this; based on the ethnographic analysis we conducted as well as extensive literature research, it came forward that social connection and openness were fundamental elements of local culture. It seemed clear that in our aim to create a sustainable, resilient design, we must take into account those who would occupy it, interact with it, and maintain it. If the local inhabitants should feel motivated to maintain their living space, they must feel connected with it – their agency must be given central importance.

Results and reflection

This theme of connection is what our design for Komchén was built around – not only connecting people with their landscape, but also connecting people with each other, and connecting the past, present, and future. We incorporated traditional Mayan agricultural techniques such as Ka’anches (raised garden beds) as well as native vegetation which could be used as ornamentation, for consumption, or for medicinal purposes. Most importantly, we emphasised communal space as a central tenet of our design, constructing typologies for city blocks in which social areas were not just included, but integrated with the rest of the space. In this way, not only could inhabitants interact with one another in dedicated communal areas, they could also find this connection in shared agricultural beds, under the shade of native trees, and around communal water wells.

Ultimately, this workshop was an incredible challenge to each participant to think outside their own discipline, exploring unfamiliar methods and perspectives to achieve new and exciting results. The combination of different backgrounds elevated the process, enabling a true exercise in interdisciplinarity. Each team produced a unique design for each site, tailored to local needs and each finding a unique interpretation of the past and how it can shape the future.

0 Comments