Colonial legacies and art museums: Combining museum research and practice

Carolina Monteiro was involved in the Mauritshuis' first attempt to critically examine its own colonial legacy.

It is not often that one has the chance to combine theoretical and practical work when conducting a research in a determined field. Between 2018 and 2019, while conducting a Master Thesis’ research about the colonial legacies of art museums, I had the chance to work at the Mauritshuis, as part of the team developing the exhibition Shifting Image: In Search of Johan Maurits, which can be considered the museum’s first attempt to critically examine its own colonial legacy.

I have always been interested in the stories museums tell, and how these institutions are seen as reliable sources of historical and art-historical information in different countries. When starting my Master’s in Museums & Collections at Leiden University in 2018, I expected to take this interest further and decided to analyze how Dutch institutions interpret and display their representations of colonized peoples and faraway places, and most specifically of their representations of the seventeenth-century Brazilian society under Dutch rule (1630-1654).

The most emblematic figure of this period, Johan Maurits, count of Nassau-Siegen (1604-1679), governed the colony for seven years (1637-1644) and is usually referred to as a ‘humanist prince’ by historians. Largely known in Brazil as Nassau, he invited a group of scientists and artists to document the daily life of the recently captured territory in the Northeast coast of the country, generally known as Dutch Brazil. Their observations were materialized in a number of publications and artworks depicting the people, the fauna, the flora and the geography of the colony, some of which are currently displayed at Dutch institutions, such as the Rijksmuseum, the museum Boijmans van Beuningen and the Mauritshuis. The latter, one of the most important museums in the country, besides hosting the collection of stadtholders Willem IV and V, interestingly retains its name from its idealizer and former resident, the same ‘Maurits’ who governed Dutch Brazil. This essential piece of information served to guide my Master’s research, which became focused in one museum and some of its artworks that are intrinsically linked to the history of the Dutch occupation of Brazil.

I made my first contact with the institution through curator Lea van der Vinde, whom I approached to talk about my research after attending one of her lectures at the museum. Lea was immensely kind and demonstrated a real interest on the topic, what led to us scheduling my first visit to the museum’s library. I believe I was at the right place and at the right time for conducting this specific research. Just a few months back, the Mauritshuis had been heavily criticized for removing a replica of the bust of Johan Maurits from the foyer, thus talking about colonial legacy was definitely a hot topic inside the institution. After reorganizing room 13 to display some of their most significant works related to Dutch Brazil, the institution saw fit to bring a 1986 replica of the bust of Johan Maurits to the depot, for its display in the foyer was confusing to visitors and difficult to contextualize. The absence was publicly noted a few months later and the museum was accused of trying to erase its (colonial) history. The episode caused a frenzy on social media, with the criticism escalating to a political tone, even the Prime Minister, Mark Rutte, gave his opinion on the matter.

This issue was paramount for my research, which revealed the institution, among the shower of backlash caused by the removal of the bust, had actually already started to think more deeply about its ties to Dutch Brazil. An exhibition about the figure of Johan Maurits and his current social perception was already being planned and an internship vacancy was open in the Collections department for conducting research on the topic. Having successfully applied for the position, I was able, not only to continue my Master thesis research on the representation of seventeenth-century Brazilian subjects, but also to experience the daily life among the curatorial and educational teams dealing with the sensitive topic of colonialism. For three months I researched the construction of the image of Dutch Brazil and Johan Maurits in Brazilian historiography and the connection between museums’ traditional discourse and the lack of diversity in the sector.

With the end of the internship in the beginning of 2018 and the exhibition approaching, I was offered a position as a Junior Researcher to continue working towards building the content of the show and its adjacent events. By working closely with the chief curator, Mrs. Van der Vinde, I had the opportunity to deal with different aspects of the curatorial work, from diplomacy to decision-making processes, as well as research and content making. Together with the educational team, I was able to create an original tour to accompany the exhibition, aiming to rethink the history of Dutch Brazil through the use of the museum space and specific artworks.

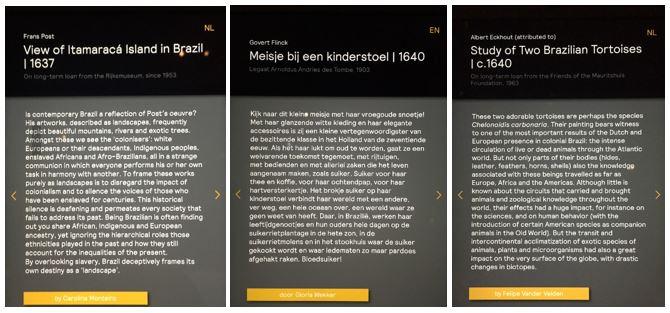

Starting from the principle that for years the museum had been promoting an enlightened view of Johan Maurits as a patron of the arts and science, the exhibition Shifting Image intended to open up the debate to a more contextualized view of his role as the governor of a colonized territory whose economy was based on production of sugar-cane and the exploitation of people, especially from African descent. Committed to present different perspectives around the artworks and the history of Dutch Brazil, the show (held from April 4 to July 7, 2019) counted with more than 40 collaborators who created their own label for the eleven artworks on display. Historians, anthropologists, as well as dancers and politicians shared their different opinions on the matter, intertwined with the interpretations of the museum staff, including myself. Among the participants were Leiden University professors Mariana Francozo, Karwan Fattah-Black and Michiel van Groesen. Instead of presenting the usual inflexible museum label, each artwork counted with four to six different interpretations, presented on an interactive display.

Colonial Representations of Brazil and their current display at Western museums, my MA thesis submitted in the end of the first semester of 2019, marked, not only a full circle between my research and museological practice at the Mauritshuis, but also served as the starting point of my academic career as a PhD candidate in Archaeology. The experience I gained by working at a Dutch art institution in the very same topic of my academic research helped me understand the steps encompassing museum decision-making regarding sensitive topics. It also made my research more substantial, while putting me in contact with contemporary researchers and museum professionals working on similar subjects.

0 Comments