Fieldwork in a flood: working with natural disasters

Chi Zhang's fieldwork was disrupted by catastrophic flooding in Henan Province, China.

For archaeologists and anthropologists, fieldwork is an important experience that needs thorough preparations. However, even the most thorough preparation cannot prevent a fieldwork from unpredictable accidents. Natural disasters, such as floods, earthquakes, hurricanes, are probably the most horrible scenarios for a field anthropologist or archaeologist.

During my fieldwork in Luoyang, Henan Province, China this July, I came across a flood caused by heavy rains. Hereby I would like to share my experience.

Encountering Flood

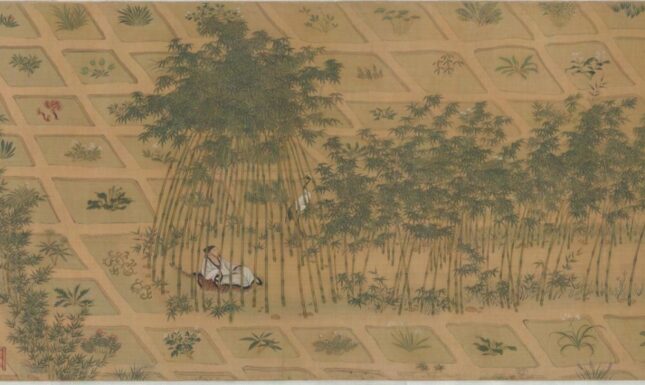

My doctoral research is about historic houses, or historic residences, which are old physical dwellings that people used to live in. My fieldwork in Luoyang was designated to examine a site of historic house named Du Le Yuan (“the Garden for Solitary Enjoyment”), the residence of Sima Guang (1019-1086 AD), a Chinese historian and politician in the Northern Song Dynasty (960-1127 AD)

However, a record-breaking heavy rain has rapidly swept the whole Henan Province, which also threw my original fieldwork design into disorder. On my way from the airport to the hotel, the driver warned me:

“We haven’t seen such heavy rain in many years…I just heard some places are even buried in mud slides caused by this heavy rain…The highway will be closed soon. You’d better stay indoors in these days.”

He was right. As the maximum rainfall per hour has reached 201.9 mm in the capital city of this province, the rains immediately became devastating floods. Concerning that any outdoor activity would be too dangerous, I listened to the driver’s advice, staying in the hotel room for two days.

Cyber anthropology in a room: prying into social media

Although being stuck in the hotel room, I could not easily give up my fieldwork. Thus, I turned my “field” from reality to virtual, communicating with my respondents through social media, mostly on WeChat (a Chinese instant messaging application).

During my staying in Luoyang, I was introduced to Xu, a resident from S Village in Luoyang. Having added Xu on WeChat, I was quite astonished by his enthusiasm for Du Le Yuan in the past years. This enthusiasm could be clearly perceived even through a first impression on his WeChat account: a profile photo using a painting of Du Le Yuan and a WeChat ID named after this ancient site.

Clicking into his social posts, Xu’s enthusiasm in the past several years is even traceable. A number of his blogposts are related to Du Le Yuan and its original owner, Sima Guang. In this cyberspace, Xu recorded a local history of the site, shared his explanation in related manuscripts, and narrated his feeling about Sima Guang’s poems.

Social media provides a virtual space, enabling us to understand our respondents in a short time. However, this “cyber anthropology” is probably just complementary expediency when face-to-face communication is not possible. An instant reply cannot be assured, leading to a lack of timeliness.

A reflective autoethnography

Although the flood has brought some inconvenience to my fieldwork, I was already favoured by fortune compared to those who lost their family and home in this ruthless disaster. As Luoyang is not the center of the flood, the city was not strongly influenced.

Being a young scholar in heritage studies, and meanwhile an anthropologist means that “Anthropos” (ancient Greek “mankind, human”) is the center of my research. Nonetheless, huddling myself in front of the hotel television, I could actually do nothing but witnessing the increasing number of victims. As anthropologists, how could we care and help our “anthropos” in such a natural disaster? With this question haunted in my mind, I started to conduct my fieldwork in reality.

After the flood receded from Luoyang, Xu and another respondent brought me to the site Du Le Yuan. We crawled the muddy slope, with our shoes sinking in the flood-scoured mud. Despite this, my elder respondent, Xu, strenuously stood on the mud, with his eyes a bit wet: “Here we are, where Du Le Yuan is!” Through his wet eyes, I could feel a sentimental connection to heritage, a connection resilient to any natural disaster.

As young scholars in heritage studies and meanwhile anthropologists, how could we care and help our “anthropos” in such a natural disaster? Perhaps we could recognize such a sentimental connection that connects people to their past, present, and future, and delve into its resilience to natural disasters.

(To protect the privacy of my respondents, the village name in this article is a pseudonym, and the respondents are written anonymously or only in their surnames.)

0 Comments